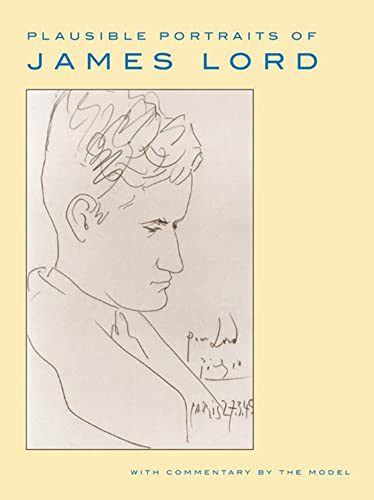

Plausible Portraits of James Lord: With Commentary by the Model - Hardcover

Incisive reflections on more than twenty portraits of the author by some of the greatest artists of the last century

Over the course of his life as a friend and confidant of artists and collectors, and as a lover of art himself, James Lord has written some of the best accounts we have of modern aesthetic genius; his biography of Giacometti was widely acclaimed for succeeding, in the words of one reviewer, "in every way as one of the most readable, fascinating and informative documents, not just on an artist, but on art and artists in general" (The Washington Times). And yet through his connection with the great artists of his day, it was inevitable that Lord would himself become the object of the artist's gaze. In fact, from the time he was a young man, Lord sat for many of the major and minor painters and photographers of his day, including Balthus, Cocteau, Cartier-Bresson, Freud, Giacometti, and Picasso―in all but one case at the artist's request. In Plausible Portraits, Lord gathers, alongside these images, his reflections, penetrating the mind of artist and model alike in a sequence of illuminating double portraits of two masters at work.

"synopsis" may belong to another edition of this title.

PICASSO Pablo Picasso was the preeminent portraitist of his period. In terms merely of quantity he was probably the preeminent portraitist of all time. And from the first, the features he most consistently commanded his talent to portray were his own. Already well before the age of twenty he had produced self-portraits inscribed, "I, the King." His passionate infatuation with self-representation knew no boundary, and over the coming three-quarters of a century thousands of images of himself in various guises spilled spontaneously from his fingertips. Even when he was portraying his wives, mistresses, children, friends, and casual passersby, he usually did so in such a manner that they were recognizable initially as Picassos and almost incidentally as individuals. Still, he could create arresting likenesses when he chose to. Indeed, it may almost have seemed that when he chose to he could create almost anything. In fact, he was sometimes heard to exclaim, "I'm God! I'm God!" This was even more exalting than to be king, and self-portraits were certainly to be viewed as objects entitled to devout veneration as the artist came closer and closer to the ultimate desecration of the model. His hubris, however, did not vouchsafe the immortal doom of atragic hero. He was too frightened by death to live on as a mythic figure. For all the illusory glory of his own lifetime, he had made so extravagant an outlay that even the fortune of the wealthiest artist in history could defray not a tithe of a tithe. Immense amounts of money have been paid for a Picasso self-portrait, but there precisely is the pitiless paradox. About the man's genius there is no question, and yet his commitment to the timeless truth of art was never sufficiently selfless to beget an artist able to further art's inherent capacity to become the redeeming element in human experience. This is not to imply that Picasso added little to the spiritual adventure of a direly troubled century. He added much. He added astonishing works of art, as to which, however, an uncertain future has still to make enduring assessments. He added an insatiable, almost maniacal and abject hunger for fame, leading to such a craven failure of integrity as fatefully falls upon a man--formerly the outspoken hero of creative freedom--prepared to support and praise without a murmur of remorse during the final third of his long lifetime a regime never surpassed for obscene evil: the Soviet Union. He added, when far too much has already been said, when what has been done has parlously been overdone, contradicted, exaggerated, and made meretricious, he added in a word, Picasso. The quest for the self secreted behind that name played upon an imperious disposition to invent rather than to discern the unique and enigmatic human who gazes inscrutably back from behind those famous eyes so repeatedly portrayed as Picasso, Plato, Praxiteles, Bacchus, and Adonis, the philosopher, the clown, minotaur and toreador, harlequin, painter, poet, lover, juggler of beauty and ugliness, a man of whom everyone has heard but nobody knows, creative daredevil who plays metaphysical tricks on naïve mankind, leaving in his wake works of art that do--or do they?--suspend all doubt in regard to the principle of illusion. Doubt, indeed, was Picasso's principal plaything, because he, all alone in his omniscient absoluteness, put an end to five hundred years of lovely confidence in the redeeming ideal of art as the lifeblood of the whole human community. Overnight the quest for the self could successfully be completed by the simple assertion, "I do, therefore I am." No cerebral activity was required. The offspring of those who had been scurrilous about van Gogh now crowded forward to consecrate excrement alongside nothingness in the pantheon of creative plenitude. Picasso is reputed to have remarked that he could draw as well as Raphael. Even as a bon mot it was no good. He could convincingly imitate Ingres if he felt like it. He could even sometimes impart to a tangle of lines the quick of life. He was amazing. But in and of and for and by himself he allowed his genius to use him in order to substantiate the dehumanization of the very ground upon which he had chosen to stake his own humanity and its otherworldly perpetuation. He was too sly not to know this, and the knowledge is pathetically self-evident in the pitiful self-portraits of the artist's final years. He was terrified of dying, having been too callous during his lifetime to envision the beauty of oblivion. Where in his Inferno Dante would have placed Picasso is a matter for tantalizing, somber, and lamentable conjecture. Why today I take the liberty of articulating notions so long ago left idle is probably a simple surrender to the temptation of having a final fling with half a century's cumulative but supererogatory musings, which, of course, have everything to do with the possession,the pertinence, and the power of portraits, their maker and their model. Of all such intimations, to be sure, I had not the slightest inkling in war-worn Paris in the month of December 1944, when I braced my brashness at the pinpoint of Picasso's doorbell. As to the durable changes in my life brought about by pressing it, I have quite sufficiently described them elsewhere, albeit without dwelling very much on the issue of portraiture per se, though the two drawings made of me by Picasso are by no means unmentioned. The treacherous seductiveness of a portrait had never before tempted my introspective vulnerability. To be sure in that long-ago, grisly autumn I had lived with the propinquity of death as never before or after. My own transformation into a corpse did not at the time seem likely, of course, because soldiers take their personal survival for granted. Besides, I was seldom in any danger. Dying, however, was very much on my mind, in my dreams and before my eyes, a single visit to a field hospital scarring one's visual remembrance more than enough to last a lifetime. But I looked for forgetfulness, too, in the belief that art could confer the only kind of immortality worth living for. Rembrandt, Beethoven, Balzac. Oh, I scanned the heavens, didn't I? And yet it's true, it's absolutely true I had no idea what my mind was doing, but it did believe in the grand hypothesis of greatness if I could but approach it, see it for myself, touch it, even possess the proof. Yes, my outrageous desire was merely to amount to more than James Lord could ever hope to, foolish boy. The really redeeming geniuses, however, were inconveniently immortal already. Nevertheless there was one who certifiably did live and create in the very land where worldwide insanity had sent me. So there was someexistential cause concealed within the purpose, not to mention the propriety, of pressing Picasso's doorbell. The first portrait which at my request he, or anyone else, for that matter, ever made of me was drawn during lunch in a restaurant called Le Catalan several days after the fateful tinkle of the bell. Genius is wont to fight shy of conquests that are too easy. To capture a likeness is one thing, to accept its surrender is very definitely another. I had made the acquaintance of a great artist, the most famous and emblematic of his era, and been given a portrait of myself from his hand, tangible proof--was it not?--that my person had commanded the scrutiny of a genius. Such consummation, I realized, comes to very few, and so I might naturally have assumed that in this domain of craving I had nothing further to desire, that my quest for vision into the self had gloriously been consummated. But no, this was only the beginning. To start with, Picasso's portrait was a piercing disappointment. The secret self had evidently--and blindly--foreseen something altogether more comprehensive. In my diary I described the drawing as "A quick little sketch dashed off during lunch." That it happened to be a Picasso did not appear to provide what was wanted in the realm of revelation. The artist's attention and creative faculties clearly had not been engaged very deeply either by his model or by his drawing while I sat before him in the restaurant. I saw in my portrait evidence principally of haste and indifference--its inadequacy, not my own. The rendering of the GI-cut hair, the ear, the body, eye, and eyebrow, to be sure, is perfunctory. Not so the profile, however, which is aquiver, especially the mouth, vivid with feeling. And I didn't possess the insight to see what, in fact, I had beensearching for. As a likeness, it's true, the portrait lacks much resemblance to the model. However, on the evidence of his drawing, Picasso appears to have glimpsed in me something similar to my own sentimental view of his Blue Period pictures of wistful harlequins and romantic acrobats, several of whom I'd fallen in love with five years before. The pensive, slightly melancholy, ambiguous aspect of my profile, and in particular the physically awkward but aesthetically effective depiction of the left shoulder hunched upward before the chin, seemed designed to compose an image imbued by the same narcissistic pathos I had thought to discern in Picasso's youthful art as a reflection of my adolescent self-indulgence and sensual desperation. Perhaps it's just as well that I didn't yet perceive what pursuit had led me to the rue des Grands-Augustins or suspect what wizardry enabled Picasso to see what I really wanted and give it to me by making a portrait so peculiarly like an evocation of his youth, not mine. In the catalogue of the 1939 exhibition whereby Picasso had first gotten me excited, I had underlined a statement by the artist: "A picture lives a life like a living creature, undergoing the changes imposed upon us by our life from day to day. This is natural enough, as the picture lives only through the man who is looking at it." He might have done well to add that the man who is looking is looked at. And I see now, fifty-eight years later, that that first portrait of me by Picasso makes a more visible demand upon the reality and vision of an old man than ever could have been expected of a youth. The youth, meanwhile, having been relegated far from the battlefield to a bourgeois backwater in Brittany, engaged nonetheless in mental strife with his craving to be portrayed once again--and to his enduring satisfaction this time--by the baffling genius in Paris. Never for an instant did it occur to me that I might not chance to find myself once more in the presence of the indispensable artist. Nobody, I believe, having met him but once face-to-face, or knowing only his pictures, after all, could thereafter realistically foresee a time when Picasso might cease to loom over the perspective of things to come. As a prelude to dreams which I foreordained to be obedient, I puzzled and pondered about an infallible stratagem that might work like sunshine when in reply to my request Picasso would inevitably remark that his mastery of portraiture had been exercised to my advantage already. The only thinkable retort, I decided, would have to be misfortune. Unspeakable, ambiguous misfortune, its specific nature best left to the conjecture of an incomparable creator. This, of course, was before technology had begun to destroy the human imagination. To a man who lived in intimacy with the likes of Ovid and Aristophanes, the mere suggestion of misfortune could hardly be set aside as an effective cause. And it worked like magic, which it was, when eventually I asked him in front of three or four other men to draw once again my portrait. The conclusive inducement, I think, was nothing better than audacity, the stark, staring audacity of ingenuous awe. This time there was to be no mistake about the size of the paper I had brought with me or the quality of the pencil. But there must have been a determining difference. Not in my physical appearance, I assume, but in an inner one. Several months had passed, during which, dismissed from Brittany, I had been involved in the frantic misery and accidental fates of prisoners and victims of war, and this had further afflicted what equanimity I had left. Who can say thatthis was visible? It so happened that at the very same time Picasso was working on an enormous painting which depicted a scene of atrocity, dead bodies in a ghastly heap, limbs disjointed, gruesome features twisted and contorted, a vision appallingly reminiscent of the prison camp so recently my place of "work," where weeping men clawed for a sip of water while others died of hunger in the mud. Neither I nor the artist referred to such aspects of civilization's dismemberment, but it existed. He took the pencil, folded in half the sheet of paper, and told me to be seated on a chair some six feet away. My left profile was turned to him, so I couldn't tell how intently or how long he looked at me before beginning to draw. Not very long, because I quickly heard the pencil hissing on the paper, slowly at first, then faster, as if with a deliberate fury, while I hoped that this would go on forever, and then the whole business was done in less than five minutes. Picasso tossed the paper onto a nearby table. The witnesses crowded in front of me to see what had been drawn, and Sabartes, the artist's dour secretary, cried, "The latest masterpiece!" That exclamation embarrassed the model, but apparently no one else, least of all the artist. When I saw the drawing, I saw instantly--and at the time, perhaps, only--that it was what I had wanted. It was large, it looked like a likeness, and bore no resemblance whatever to the sketch dashed off in a restaurant sixteen weeks before. I thanked the artist as he rolled up the drawing and slipped a rubber band around it. For all response he simply shrugged. When I went toward the door to leave, Picasso came with me and kissed me on both cheeks as I bent toward him to say goodbye. This certainly, was the beginning of an intimidating sort of friendship that was to last for a decade. I acquired a portfolio to protect the portrait, plusits predecessor, and carried them with me everywhere until the war was over, then back to America, then back to France, where I will remain as long as Paris survives. It has been with me always, though I gave the original ten years ago to the Picasso Museum here, a gesture that merits some musing, but to forestall complete privation I had an excellent facsimile made, very nearly indistinguishable from Picasso's own handiwork when framed under glass. So I have not lost my relation to a likeness. A masterpiece is a work of whatever sort produced by an unquestioned master of the discipline entailed in its production. Whether or not Sabartes was right in so describing Picasso's second portrait of me I dare not say, but he was a lifelong connoisseur of the artist's work, and later, when we had become friendly, he once told me that he knew of no other portrait similar to mine in its bare linear volume and power limned with such sharp clarity of feeling conveyed as a kind of gleam refracted from my young sensibility, adding, moreover, that no other artist living--or dead?--could have produced an equivalent aesthetic vision of tenderness and determination. Oh, he added, he seemed to recall some vague resemblance to a sketch of the artist's son, Paulo, poring over a schoolbook, drawn about 1935 or 1936, but it was not nearly so stark and spirited. These were not his exact words, but they accurately enough convey the sense of what he said that summer afternoon and all I later recorded in my diary. Sabartes was a Romantic poet manque, his life entirely dependent on Picasso's, who treated him with affectionate derision, and when he showed me with tremendous pride the portraits drawn of him by his employer, I sad...

"About this title" may belong to another edition of this title.

- PublisherFarrar, Straus and Giroux

- Publication date2003

- ISBN 10 0374281742

- ISBN 13 9780374281748

- BindingHardcover

- Edition number1

- Number of pages224

- Rating

Buy New

Learn more about this copy

Shipping:

US$ 4.25

Within U.S.A.

Top Search Results from the AbeBooks Marketplace

Plausible Portraits of James Lord: With Commentary by the Model

Book Description Hardcover. Condition: new. New Copy. Customer Service Guaranteed. Seller Inventory # think0374281742

Plausible Portraits of James Lord: With Commentary by the Model

Book Description Hardcover. Condition: new. Buy for Great customer experience. Seller Inventory # GoldenDragon0374281742

PLAUSIBLE PORTRAITS OF JAMES LOR

Book Description Condition: New. New. In shrink wrap. Looks like an interesting title! 1.64. Seller Inventory # Q-0374281742

Plausible Portraits of James Lord: With Commentary by the Model

Book Description Hardcover. Condition: new. New. Seller Inventory # Wizard0374281742

Plausible Portraits of James Lord: With Commentary by the Model

Book Description Hardcover. Condition: new. Brand New Copy. Seller Inventory # BBB_new0374281742