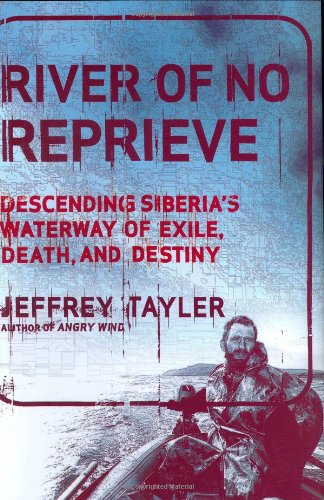

River of No Reprieve: Descending Siberia's Waterway of Exile, Death, and Destiny - Hardcover

Synopsis

One of today's most intrepid writers chronicles a deadly trek through the legendary region that gave birth to the gulag and gave Siberia its outsize reputation for perilous isolation.

In a custom-built boat, Jeffrey Tayler travels some 2,400 miles down the Lena River from near Lake Baikal to high above the Arctic Circle, recreating a journey first made by Cossack forces more than three hundred years ago. He is searching for primeval beauty and a respite from the corruption, violence, and self-destructive urges that typify modern Russian culture, but instead he finds the roots of that culture―in Cossack villages unchanged for centuries, in Soviet outposts full of listless drunks, in stark ruins of the gulag, and in grand forests hundreds of miles from the nearest hamlet.

That’s how far Tayler is from help when he realizes that his guide, Vadim, a burly Soviet army veteran embittered by his experiences in Afghanistan, detests all humanity, including Tayler. Yet he needs Vadim’s superb skills if he is to survive a voyage that quickly turns hellish. They must navigate roiling whitewater in howling storms, but they eschew life jackets because, as Vadim explains, the frigid water would kill them before they could swim to shore. Though Tayler has trekked by camel through the Sahara and canoed down the Congo during the revolt against Mobutu, he has never felt so threatened as he does now.

"synopsis" may belong to another edition of this title.

About the Author

JEFFREY TAYLER is a correspondent for the Atlantic Monthly and a contributor to Condé Nast Traveler, Harper’s Magazine, and National Geographic. He is the author of many critically acclaimed books, including Facing the Congo, Angry Wind, and River of No Reprieve.

Excerpt. © Reprinted by permission. All rights reserved.

1 The plane was half empty, the air inside muggy and rank, redolent of sweat and latrines. A couple of hours into the all-night flight from Moscow to Bratsk, where I hoped to find a car or truck to take me three hundred miles northeast through the taiga to Ust’-Kut, I wiped away the condensation and peered groggily through the porthole. Below the jetliner, a Soviet-era TU-154 seating some eighty passengers, a darkly verdant carpet of forest laced with silver- gray rivers Siberia swept away toward the horizon under a pale sky midnight on the twentieth of June.

Always an expedition’s first hours hit me the hardest, leaving me the nonplussed victim of my own wanderlust and obsessions. My distress began at Domodedovo Airport, in southeastern Moscow, earlier that hot, humid evening. Jostled by red-faced travelers dragging checkered vinyl sacks and plastic-wrapped suitcases for flights to Siberia, I had stood on the dusty linoleum with my wife near security control. Her eyes watering and wide open, she pressed her trembling cheeks to mine. We had been rushed on departure from our apartment and had not managed to sit for a few moments of silence, hands clasped and eyes locked, as Russian custom required for good luck on such a journey. Being Russian, and knowing her country, Tatyana distrusted everything Russian. I knew her fears. She felt she might be touching me for the last time before releasing me into a semibarbarous hinterland beginning just outside Moscow and stretching into infinity, all forest, bog, and low mountain, peopled with drunks and thugs, divided into satrapies ruled by petty tyrants who would love to get their hands on an American. Her fears were exaggerated, I knew, but I no longer argued with her to make positive predictions before an undertaking in Russia is to tempt fate.

They called my flight. I pulled away from her, shouldering my bag. She stood at the guardrail and watched me pass through security, alarm washing over her face as an airport policeman pointed to my knapsack and asked me to open it. He pulled out my maps of the Lena. Largescale maps are still viewed as quasi military in Russia. What would a foreigner need them for, if not espionage, he asked? Expedition? What sort of expedition? What exactly was I planning to do in Siberia? And why Siberia, for that matter? During Yeltsin’s time, he probably would not have cared about maps or bothered detaining me. Now, with Putin in power, security officers did whatever they wanted and were as suspicious as they often were greedy. How much money was he going to demand to let me go? He questioned me for so long that I began worrying whether I would make the flight. Only mention of my affiliation to Dmitry Shparo won my release.

Finally free, I waved goodbye to Tatyana, jogged to the gate, and just made the bus that took me on a rattling ride over heat-warped tarmac and out to the plane. Now, gazing through the porthole, I started to doze off. But soon the sky shaded into azure and swords of sunlight from a point on the earth’s sharp rim stabbed my eyes. Before I knew it, I was standing in Bratsk’s dank terminal barn, swatting mosquitoes, dazed by the lack of sleep and the five-hour time difference, waiting next to a derelict luggage conveyor for my backpack and other gear to appear, with three or four drunken passengers who had also checked bags. (To avoid theft, most in Russia prefer to carry on.) Luggage retrieved, I then found myself haggling outside in the sun with the sole driver on the lot: a shaved-headed, pug-nosed, paunchy man in his late forties. His Russian’s aspirated g’s indicated Ukrainian provenance. With his crude mug and scarred hands, he looked like a criminal, but then out here driving was serious business; vehicle repairs in Siberian frosts often involved getting your damp bare hands frozen to steel and losing shards of skin. He had a peasant frankness about him that I found reassuring.

His taxi was a gray, listing Volga sedan of a model that I had seen only in old Soviet movies.

Ust’-Kut?” he said. Christ, we’ve had rain and the road’s all mucked up. But, well . . . well, okay, hop in.” He introduced himself as Volodya. We drove off the lot, rocking onto a narrow, beat-up highway running like an alley through the forest. I tried in vain to sleep. The violent ascending road, a swerving track of gravel in parts and mud in others, cut through a looming taiga of scraggly larch and majestic spruce, lucent with light flooding through broadly spaced boughs. Now and then logging settlements appeared on the hillsides, above rushing streams blue with the sky, glittering with the sun.

Look at this mud!” said Volodya, wrestling with his wheel. They daare call it a federal highway’! Just this winter wolves tore a woman to pieces out here.” He was smiling with pride. Siberia!” When did you move here from Ukraine?” Back in the seventies. I came to work at the dam power station in Bratsk. I’m too old to go home now, and anyway, I like the peace and quiet here. You can’t leave Siberia once you learn to live here.” The news came on the radio. I waited for the now customary litany of Putin’s daily meetings and wise pronouncements, but they never came. Local events filled the airtime.

You don’t get national news out here?” I asked.

Hell, we don’t care what they do in Moscow,” Volodya declared.

Whatever they decide in the capital, whatever wonderful changes they say are coming to us, out here nothing changes. Our local deputies are always fending off some inspector come from Moscow to make trouble. Either that or they’re out for themselves. What do I care about Moscow, tell me!” A minor explosion sounded from the front of the car. A tire had blown out. We stopped. Volodya continued his tirade as he wrestled the spare free from debris in the trunk. However, all politicians everywhere, even here, are just out for themselves . . . But who cares, and who does anything about it? But let some poor drug addict break into an apartment to get money for his fix. They throw him in jail for stealing a few rubles. Look, I don’t need the materik” the mainland,” as Siberians call European Russia. A fish rots from the head,’ we say. Get it? See why I don’t care about hearing Moscow news? Here I have my peace and quiet. No rotten smells.” After we finished changing tires, I stepped away from the road and walked to the edge of the taiga. Here it was all birch, leaves so green they seemed to glow, and trunks gleaming as if painted with fresh coats of white and zebra-slashed with black from base to crown. Bumblebees buzzed around my ankles; a giant horsefly sailed out of the foliage and took to circling me. Soon I was standing in cloud of fat bugs, all swirling slowly as if drunk from the heat and sun.

Hey, get away from the woods!” Volodya shouted. You can get a tick in the grass and catch encephalitis! You could be dead in a day out here! Siberia!” I trotted back to the car and jumped in for the last three hours of jolts and bumps to Ust’-Kut.

For most of Russia’s history, nothing more than a mud track, which north of Mongolia and China disappeared into bog and forest, connected Saint Petersburg and Moscow to the Far East. In 1891, however, the tsar ordered the construction of the Trans-Siberian Railway. Once completed twenty-five years later, it would run almost six thousand miles from Saint Petersburg to Vladivostok on the Sea of Japan. Yet even before the Trans-Sib was finished, Russians began suspecting that in wartime the railway, paralleling the Chinese border in places, might be vulnerable to attack. Desiring a more secure and thus more northerly line, in 1911 the government started work on BAM the Baikal-Amur Magistral’ (trunk railway). To be built at a strategically sound distance from the frontier, BAM was to carry Siberia’s wealth in timber, coal, gold, and other minerals safely back west to the materik, while opening up the region north of Lake Baikal to settlement. Plans metamorphosed, waxing and waning with their political expediency (one pre-Soviet scheme even had BAM connecting easternmost Siberia to Alaska) but in any case, over the coming seven decades some two thousand miles of track were laid to branch off the Trans-Sib at Taishet (2,600 miles east of Moscow), reach Ust’-Kut (its northernmost station, another 375 miles east), and wend across the taiga to finish at Sovetskaya Gavan on the Tatar Strait. Crossing through bog and over permafrost, BAM constituted the largest and most complex construction project the Soviet Union ever undertook. To build most of it, the government, as short of cash as ever, initially had to resort to the deployment of troops and gulag prisoners, Japanese POWs and indentured students. Later, in the 1960s and 1970s, Soviet propaganda persuaded tens of thousands of young workers to head east and advance the project. Owing to secretive and shoddy Soviet accounting, BAM’s true cost will never be known, and large segments remain incomplete. Still, in a few decades BAM transformed Ust’-Kut from a village of twelve thousand into a town of seventy thousand, and longtime residents past the age of forty I was to meet sang the joys of being young and strong and full of hope in BAM time, when they were engaged in the great project of putting Siberia’s riches at the service of the mighty Soviet state. In Ust’-Kut’s heyday two million tons of freight timber, minerals, and fish shipped by barge up the Lena, and supplies brought from the materik by rail for the settlements downriver, as far as Tiksi passed through the town every year. Now, with the death of Soviet planning and construction projects, scarcely 500,000 tons pass the docks per annum.

After paying Volodya and wishing him Godspeed, I checked in to the Hotel Lena on the poplar-lined square opposite Ust’-Kut’s old river station. The station was a teal green Soviet baroque palace of sorts, attesting to pretensions of the past: a transport hub for the Communist taming of Siberia had to project a grandeur in which the proletariat could take pride. Now the building exuded tranquility in homey decay, and I recognized it with a tinge of nostalgia as where I had begun my ferry trip to Yakutsk four years earlier, on a morning cooled by a breeze fragrant with spruce sap and pine needles. If on the plane I had been disoriented and despairing, here, now, I felt I was coming home.

This sensation only increased as I unpacked in my room. My blood began stirring, yet not really in anticipation of the expedition. Rather, every time I leave Moscow to venture into the glush’ (the outback”; the noun, the root for the adjective glukhoy, or deaf,” conjures up the dreamy tranquility of a Russian birch grove), an inspiring élan steals over me once the shock of departure passes. In the glush’ life is slow, people earnest, the air fresh, and the nights placid balm for a Moscow resident’s soul.

I would relish my last hours of solitude. My guide, Vadim, wasn’t due to arrive until the day after next, so I left my room to find a seat at one of the several cafés on the square. There, in the lambency of a summer’s eve, shaggy poplars shed seed puffs over green and red café tarpaulins painted with Heineken and Coca-Cola logos. Clustering near the station on a warped tarmac, amid unkempt grass lots intersected by cracked sidewalks, the tarpaulins looked like the remnants of a circus long gone. Most of the tables stood outside them, in the open air.

I pulled out a chair at one of them and sat down. Beyond the greenwalled station, the Lena surged a rippling band of bluish silver, reflecting the sky of the white nights. The river here was a quarter-mile across, narrower and faster than it would be ahead, and it tugged frothily at a buoy in midstream. From radios playing on the opposite bank, in the yards of izbas, or traditional Russian log cabins, old Soviet dance tunes drifted over to us, amplified by the waters. It seemed impossible to imagine now that there had ever been a Stalin, or a time when the town had been the port for gulag land beyond, in a country called the Soviet Union.

A waitress approached, creamy-skinned, cat-eyed, dressed in a frumpy blue cashier’s smock and jeans and flip-fl ops. Her long russet hair was pinned up in a bun, with locks dangling over her pale and fleshy cleavage. She didn’t greet me but rather lingered by my table, drawing circles with her index finger on the dust, as if waiting for an indecent proposal. I asked her for a beer. Saying nothing, she sloughed away, rattled around behind the bar, and returned to me smiling, a bottle in hand.

Most of the socializing on the square, I noticed, took place just off the café grounds, where people stood drinking at a nearby kiosk rather than pay for a café seat. Loud young men, their voices hoarse from smoking, their skulls shaved, gathered in threes and fours and guzzled beer from two-liter brown plastic bottles and cursed and laughed. On the sidewalks pretty young women pushed baby carriages, navigating the buckled cement, sipping bottles of beer or sucking on cigarettes, chatting, brushing the poplar puffs from their eyes pale blue eyes, jade eyes, honey eyes, set in regal faces. In 1848 the tsar had exiled Polish gentry here after the anti-Russian revolts in Poland surely these women were their descendants.

By a charred brazier near my table, an Armenian kebab-maker stood turning spits of pork chunks roasting over coals, fanning the flames with a sheet of cardboard. Sniffing the meat, I developed a ravenous appetite and ordered some. Happy Nation” then crackled through the loudspeaker, a song that took me back to my early days in Moscow, halcyon days for me, days of discovery and risk and erotic adventure in the summer of 1993. There was something fitting in this. Though the firebrand revolutionary Leon Trotsky didn’t enjoy his time in exile here (the locals never cottoned to the aloof intellectual), Ust’-Kut had been known as a party-hardy haven since the early seventeenth century, when Pyanda’s bedraggled Cossacks arrived after years of sailing down whitewater tributaries. Finally, on this beatific spot of land, they could rest and have fun. They named the tributary entering the Lena here Kut,” from kutit’, to carouse”; and carouse they surely did, intermarrying with local Evenk women, peaceable, teepee-dwelling animists. Popular lore has it that the name Lena” itself came not from Yakut or Evenk but rather, in the spirit of kutit’, derived from the verb polenit’sya, to be lazy.” If this isn’t true, Lena,” by coincidence the diminutive of the Russian Yelena” (Helen), has a soft feminine ring to it.

Mosquitoes now danced thick against the sky. The cook brought me a plastic plate laden with kebabs, a daub of adzhika hot sauce on the side, and I dug in. Savoring the meat, I gazed away from the river and into town, out onto the crumbling five-story cement apartment blocks built during Ust’-Kut’s boom years.” From their midst a black Opel careened toward the square, its sides painted with lizard-tongue flames, Russian rock blaring from within. A gray militia van followed and pulled up alongside. The officers, billy clubs in hand, got out and peered at the young men inside. The Opel peeled out, forcing a young woman to yank her baby carriage out of the road; soon, by the station two teens were scuffling. In Russia, during the evenings, even in the glush’, public places are often more unsafe the later it gets: vodka and beer mix to liberate anger and charge the air with tension.

The sun set, tinting rose the gray underbellies of clouds billowing above the fir-covered sopki (the low mountains of Siberia) ranging up and down the Lena. A chill settled over the square and the mosquitoes turned in for the night. I decided to do the same.

The day after next dawned hot and h...

"About this title" may belong to another edition of this title.

- PublisherHoughton Mifflin

- Publication date2006

- ISBN 10 0618539093

- ISBN 13 9780618539093

- BindingHardcover

- LanguageEnglish

- Edition number1

- Number of pages230

- Rating

Shipping:

FREE

Within U.S.A.

Buy New

Learn more about this copy

Shipping:

US$ 6.00

Within U.S.A.

Top Search Results from the AbeBooks Marketplace

River of No Reprieve : Descending Siberia's Waterway of Exile, Death, and Destiny

Seller: Better World Books: West, Reno, NV, U.S.A.

Condition: Very Good. First Edition. Used book that is in excellent condition. May show signs of wear or have minor defects. Seller Inventory # 4867237-75

Quantity: 1 available

River of No Reprieve : Descending Siberia's Waterway of Exile, Death, and Destiny

Seller: Better World Books, Mishawaka, IN, U.S.A.

Condition: Very Good. First Edition. Former library book; may include library markings. Used book that is in excellent condition. May show signs of wear or have minor defects. Seller Inventory # 3362298-6

Quantity: 2 available

River of No Reprieve : Descending Siberia's Waterway of Exile, Death, and Destiny

Seller: Better World Books, Mishawaka, IN, U.S.A.

Condition: Good. First Edition. Former library book; may include library markings. Used book that is in clean, average condition without any missing pages. Seller Inventory # 3362297-6

Quantity: 1 available

River of No Reprieve: Descending Siberia's Waterway of Exile, Death, and Destiny

Seller: Wonder Book, Frederick, MD, U.S.A.

Condition: Good. Good condition. Very Good dust jacket. A copy that has been read but remains intact. May contain markings such as bookplates, stamps, limited notes and highlighting, or a few light stains. Bundled media such as CDs, DVDs, floppy disks or access codes may not be included. Seller Inventory # E15M-01480

Quantity: 1 available

River of No Reprieve: Descending Siberia's Waterway of Exile, Death, and Destiny

Seller: HPB-Emerald, Dallas, TX, U.S.A.

hardcover. Condition: Very Good. Connecting readers with great books since 1972! Used books may not include companion materials, and may have some shelf wear or limited writing. We ship orders daily and Customer Service is our top priority!. Seller Inventory # S_406992632

Quantity: 1 available

River of No Reprieve: Descending Siberia's Waterway of Exile, Death, and Destiny

Seller: SecondSale, Montgomery, IL, U.S.A.

Condition: Very Good. Item in very good condition! Textbooks may not include supplemental items i.e. CDs, access codes etc. Seller Inventory # 00077549361

Quantity: 1 available

River of No Reprieve: Descending Siberia's Waterway of Exile, Death, and Destiny

Seller: AardBooks, Fitzwilliam, NH, U.S.A.

Condition: Near Fine/Near Fine. 1st. 8vo. 230pp. Slight cant to spine, tade of wear to DJ. Seller Inventory # MAIN023963I

Quantity: 1 available

River of No Reprieve: Descending Siberia's Waterway of Exile, Death, and Destiny

Seller: Adventures Underground, Richland, WA, U.S.A.

Hard Cover. Condition: Very Good. Dust Jacket Condition: Very Good. First Edition. Very light shelf wear to edges and corners of dust jacket and cover and spine. Binding remains tight and pages are clean and unbent. Very good used reading condition. Used Book. Seller Inventory # 855280

Quantity: 1 available

RIVER OF NO REPRIEVE: DESCENDING SIBERIA'S WATERWAY OF EXILE, DEATH, A.

Seller: Columbia Books, ABAA/ILAB, MWABA, Columbia, MO, U.S.A.

2006 Tayler, Jeffrey RIVER OF NO REPRIEVE: DESCENDING SIBERIA'S WATERWAY OF EXILE, DEATH, AND DESTINY Boston, MA: Houghton Mifflin, c2006 First printing 230pp 8vo New hardcover copy with d/w. Seller Inventory # 73877

Quantity: 1 available

River of No Reprieve: Descending Siberia's Waterway of Exile, Death, and Destiny

Seller: George Cross Books, Lexington, MA, U.S.A.

Hardcover. First ition edition. Near Fine/Very Good (30290) . Harcdcover, near fine condition, w. v. ltly slanted sp. Cln, tight, unmarked. Dj very good, ltly rubbed, sme lt marks. Lttly sunned spot on r. In new mylar Brodart jacket. 230. Seller Inventory # 30290

Quantity: 1 available