Synopsis

"I don't like the basic philosophy that everyone is on their own, out for themselves, a kind of social Darwinism. It's bad for society, especially now. . . . Call me crotchety, but I can't help asking, whatever happened to the social contract?"

With his characteristic humor, humanity, and candor, one of the nation's most distinguished advocates for working—and middle—class families delivers a fresh vision of politics by returning to basic American values: anyone who wants a job should have one; those who work should be able to lift themselves and their families out of poverty; and everyone should have access to an education that will better their chances in life.

An insider who knows how the economy and government really work, Reich combines realistic solutions with democratic ideals: businesses do have civic responsibilities; government must stem a widening income gap that threatens to turn our nation into a two-tiered society. Arguing that Democrats and Republicans have strayed dangerously off track, Reich breaks the impasse of current politics and shows us the way to fulfill our nation's promise.

"synopsis" may belong to another edition of this title.

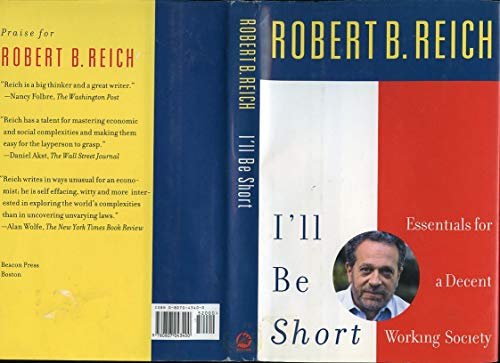

About the Author

Robert B. Reich, professor at Brandeis University and founder and national editor of The American Prospect, is author of eight books, including Locked in the Cabinet and The Future of Success. His radio commentary can be heard biweekly on public radio's Marketplace, and his writing has appeared in The New Yorker, Los Angeles Times, The New York Times, The Washington Post, The Boston Globe, and many other publications. He lives in Cambridge, Massachusetts.

Reviews

Brandeis University professor and Clinton labor secretary Reich may be vertically challenged, but he's never been short on ideas. In this brief analysis of what's gone wrong in the U.S. for ordinary citizens, Reich offers a straightforward argument. Our astonishing economic growth after World War II, he maintains, grew out of a social contract: (a) anyone who wants a job should have one; (b) those who work should earn enough to lift themselves and their families out of poverty; and (c) all Americans should have access to an education. This social contract has collapsed over decades of social Darwinism; it needs to be restored. Reich examines the roles of business (it does have civic responsibilities), government (addressing the broadening income--and wealth--gap between rich and poor is high on its list of responsibilities), and education (it's the heart of the problem). A true "family values" agenda, he urges, needs to address the problems of millions of families living from paycheck to paycheck, not thousands of families worried about "the death tax." Denial, escapism, and resignation, Reich maintains, are the main obstacles to rebuilding a decent working society. A punchy, pragmatic, articulate statement of the basic goals of progressive reform. Mary Carroll

Copyright © American Library Association. All rights reserved

Excerpt. © Reprinted by permission. All rights reserved.

Whatever Happened to the Social Contract?Not since World War II have

Americans felt so unified. We"re fighting a war against terrorism and we"re

fighting to get the economy moving again. And we"re all in this together.

Except when it comes to paying the bill.

Add the cost of fighting the war to the biggest military buildup in two decades

and extra security at home, and you"re talking real money—hundreds of

billions of dollars over the next few years. The Bush administration has also

enacted a mammoth tax cut—$1.35 trillion over the next ten years. At this

writing, the president is proposing almost $600 billion in additional cuts in

income taxes and capital-gains taxes. The bulk of these cuts—those already

enacted and those proposed—benefit large corporations and people who are

already wealthy.

So who"s going to pay? Take a guess. Middle- and lower-income Americans.

Most Americans now pay more in payroll taxes than they do in income

taxes. Payroll taxes include Social Security and Medicare payments. You

pay these taxes on the first $80,000 or so of your income (the ceiling rises

slightly every year). After that you"re home free. Bill Gates stops paying

payroll taxes at a few minutes past midnight on January 1 every year.

None of the enacted or proposed tax cuts affect payroll taxes, even

temporarily. To the contrary, they increase the odds that payroll taxes will

have to be hiked. That"s because the tax cuts, combined with the military

buildup, will drain so much money out of the Treasury that there won"t be

enough money to pay for Social Security and Medicare by the time the early

baby boomers begin retiring, about a decade from now. So payroll taxes

probably will have to rise in order to fill the gap.

Get it? Income and capital-gains tax cuts for the rich now, payroll tax hikes

on middle- and lower-income Americans to come.

Americans like to think we"re all in this together, but the fact is that the

economic fallout from terrorism is hitting some Americans much harder than

others. When the slowdown began, layoffs and pay cuts hit hardest at

manufacturing workers, white-collar managers, and professionals. Since the

terrorist attacks, a different group is experiencing the heaviest job losses: the

low-paid. Many are service workers in retail stores, restaurants, hotels, or

other tourist-industry businesses that have been hard hit. Others are

caregivers—social workers, hospital workers, elder-care workers—whose

jobs and wages are on the line as public budgets are trimmed. The economy

may be rebounding, but these people aren"t.

Government is less helpful this time around. Safety nets are in tatters.

Welfare-to-work programs made sense when work was plentiful, but without

work, those no longer eligible for welfare have nowhere else to turn. Even job

losers who still qualify find that welfare payments in most states are worth

less than before.

Unemployment insurance is also harder for them to get. Since part-time

workers, temps, the self-employed, and people who have moved in and out of

employment often don"t qualify, a large portion of the lower-wage workforce is

excluded. Many who don"t qualify are women with young children.

Meanwhile, federal programs for job training and low-income housing have

been shrunk by budget cuts. State and local governments are in no position

to step in. They"re already strapped by rapidly declining tax revenues. Rather

than beefing up social services, they"re cutting them. Rather than improving

our schools by reducing class size and offering all-day kindergartens and

after-school programs, they"re paring back. Instead of making higher

education more affordable, it"s getting out of reach for many families.

Meanwhile, more Americans are in danger of losing health care or are paying

more for the care they get.

In short, the fat years of the nineties left us woefully unprepared for a slower

economy that"s taking a particularly large toll on hardworking families and the

poor.

In the past, when Americans faced a common problem—the Depression, a

hot war, a cold war—we understood intuitively that we were all in it together.

Someone"s misfortune could be anyone"s: "There but for the grace of God go

I." Social insurance was a natural impulse, a first cousin to patriotism. It was

not difficult to sense mutual dependence and to agree on a set of

responsibilities shared by all members, exacting certain sacrifices for the

common good.

But that sense of commonality is endangered as we drift into separate worlds

of privilege and insecurity. I can"t help asking, if you"ll pardon me for

questioning our newfound unity, whatever happened to the social contract?

The sobering news is that even our ten years of economic expansion didn"t

do much for the bottom half. Sure, they had jobs, but they had jobs before

the last recession, too. The fact is, the median wage—the real take-home

pay of the worker smack in the middle of the earnings ladder—is not much

higher than it was in 1989. In my home state of Massachusetts, the typical

household ended the roaring nineties $4,700 poorer (adjusted for inflation)

than it began. And health and pension benefits for the bottom half continue to

shrivel.

Many families have made up for the steady decline by working longer hours.

The average middle-income married couple with children works almost 4,000

hours a year for pay—about seven weeks more than in 1990. But for most

mortals who do not relish what they do for pay, more hours at work does not

translate into a higher standard of living. On top of that, jobs are less secure.

Health care is more expensive. Working families are shelling out huge bucks

for good child care. And if you"ve got elderly parents who also need help, it"s

even rougher. At the same time, the upper reaches of America have never

had it so good. Their pay and benefits have continued to rise.

Look, I don"t begrudge anyone a fat paycheck or a big dividend check. But

the worrier in me won"t let go. I don"t want my boys to grow up in a two-tiered

society where they"ll have to live in gated communities. Yet that"s the

direction we"re heading in.

The problem is not that some of us are getting rich. That"s the good news.

The problem is that most of us are getting nowhere, even though we"re

working harder than ever before. We are hurtling toward a society composed

of a minority who are profiting from changes in the economy and a majority

who are not.

The consequence of this erosion extends beyond economics. It helps explain

why hard-pressed parents can"t find the time to raise their kids the way they

themselves were raised and to pass on the values they grew up with; why

voters whose family budgets pinch so tightly are outraged about government

inefficiency and waste; why even instinctively generous Americans find their

compassion toward the less fortunate flagging; why our politics have become

so angry, even sometimes ugly.

Perhaps most important are the moral consequences. Put simply, it just isn"t

right. The glaring, grotesque wrongness of what"s happening to hardworking

American families spawns despair and cynicism. It affronts our values,

mocking the American bargain linking effort and reward. It makes people feel

like suckers and gnaws away at the precious ethic of responsibility. It closes

the gate to the very poor. Ultimately, the hollowing-out of the middle class

and the creation of a two-tiered society pose a mortal threat to what"s always

been special about our country.

Why isn"t this being talked about? My guess is that Republicans don"t feel

comfortable with the topic because they don"t have any solutions they"d find

palatable. The right wing of the Democratic party has drifted toward a flaccid

Republicanism, where the basic philosophy is that everyone is on his or her

own. Corporate America isn"t particularly eager to talk about it, or to sponsor

television programs or advertise in magazines that do. But the fact is, as we

proceed with the war on terrorism, our domestic agenda is in shambles. We

need to make the case that we can only be a strong nation if the working

middle class and the less fortunate are brought along. True national security

begins with economic security.

Millions of Americans—myself included—were raised to believe in a simple

bargain: Anybody who worked hard could earn a better life for themselves and

their family. That"s anybody—not just the wellborn, not just the well

connected. Anybody with the drive and discipline to make the most of their

opportunities had a decent chance to make it. Corporate America backed the

bargain, too. Employees who worked hard and gave it their all could share in

the company"s success. If the company did well, their jobs were reasonably

secure, and their wages and benefits rose.

In the 1950s, my mother and father worked six days a week in their small

clothing shop, selling skirts and dresses to the wives of factory workers. I

remember making signs when they had special sales: cotton dresses, $2.99;

blouses, $1.00. As factory wages went up, local families had a bit more to

spend every year, and my parents" little business grew less precarious. They

went upscale. We all did better together. Growing together was the way it

worked in America.

America has got off that track. We"re growing apart—and at a quickening

pace. My parents retired before the new economy elbowed out the old. Most

of those factory jobs are now gone. Jobs like them accounted for over a third

of all American jobs in the 1950s; now, fewer than 16 percent. Many of the

old service jobs have disappeared as well. Telephone operators have been

replaced by automated switching equipment, bank tellers by automated teller

machines, gas station attendants by self-service pumps that accept credit

cards, and secretaries by computers and voice mail. Any job that can be

done more cheaply by a computer is now gone, or pays far less than before.

We can"t bring back the old economy, and shouldn"t try. But that doesn"t

leave us helpless. What we can do is create a new economy in which many

more succeed.

Earnings began splitting between the have-mores and the have-lesses largely

because of two revolutions—one in computer technology, the other in global

economic integration. The combined effect has been to shift demand in favor

of workers with the right education and skills to take advantage of these

changes, and against workers without them. Meanwhile, the unionized

segment of the workforce has shrunk. Today, fewer than 10 percent of private-

sector employees are unionized. In 1955, 35 percent were unionized. At the

same time, the real value of the minimum wage has declined. The drop in

unionization has taken a toll on the wages of men without college degrees.

The drop in the minimum wage has taken the biggest toll on the wages of

working women without college degrees.

The real puzzle is why in recent years we"ve let this happen. If the right

education and skills are so important, why haven"t we done more for our

schools? Why is the federal government cutting back on job training? Why is

college becoming less affordable? If family incomes are under greater and

greater stress, why have we let unions wither and the minimum wage

decline? Why haven"t we widened the circle of prosperity so that more

Americans have a decent shot at it? In short, why has the social contract

come undone? In the world"s preeminent democratic-capitalist society, one

might have expected just the reverse: As the economy grew through

technological progress and global integration, the "winners" from this process

would compensate those who bore the biggest burdens, and still come out

far ahead. Rather than being weakened, the social contract would be

strengthened.

Nations are not passive victims of economic forces. Citizens can, if they so

choose, assert that their mutual obligations extend beyond their economic

usefulness to one another, and act accordingly. Throughout our history the

United States has periodically asserted the public"s interest when market

outcomes threatened social peace—curbing the power of the great trusts,

establishing pure food and drug laws, implementing a progressive federal tax,

imposing a forty-hour workweek, barring child labor, creating a system of

social security, expanding public schooling and access to higher education,

extending health care to the elderly, and so forth. We did part of this through

laws, regulations, and court rulings, and part through social norms and

expectations about how we wanted our people to live and work productively

together. In short, this nation developed and refined a strong social contract,

which gave force to the simple proposition that prosperity could include

almost everyone.

Every society and culture possesses a social contract—sometimes implicit,

sometimes spelled out in detail, but usually a mix of both. The contract sets

out the obligations of members of that society toward one another. Indeed, a

society or culture is defined by its social contract. It is found within the

pronouns "we," "our," and "us." We hold these truths to be self-evident; our

peace and freedom is at stake; the problem affects all of us. A quarter of a

century ago, when the essential provisions of the American social contract

were taken for granted by American society, there was hardly any reason to

state them. Today, as these provisions wither, they deserve closer scrutiny.

To the extent that there"s been a moral core to American capitalism, it"s

consisted of three promises.

First, as companies did better, their employees would too. As long as a

company was profitable, employees knew their jobs were secure. When

profits rose, wages and benefits (health care and pensions) rose, too. In

harder times, companies accepted lower profits to retain their workers. At

worst, if a recession hit hard, companies laid workers off temporarily and then

hired them back as soon as the economy turned up. The communities where

most employees lived were also part of the contract: As long as the company

was profitable, it remained in the community—often underwriting charities

and responding to community needs.

"The job of management," proclaimed Frank Abrams, chairman of Standard

Oil of New Jersey, in a 1951 address typical of the era, "is to maintain an

equitable and working balance among the claims of the various directly

interested groups . . . stockholders, employees, customers, and the public at

large. Business managers are gaining in professional status partly because

they see in their work the basic responsibilities [to the public] that other

professional men have long recognized in theirs."

The second provision of the social contract was that working people were

paid enough to support themselves and their families. No family with a full-

time worker would be in poverty. If there weren"t any jobs or if the breadwinner

was disabled or had died, the family would be kept out of poverty through

social insurance. The nation instituted unemployment insurance, Social

Security for the elderly and disabled, aid to widows, which became Aid to

Families with Dependent Children, and Medicare and Medicaid. "From the

cradle to the grave," said Franklin Roosevelt, "people ought to be in a social

insurance system."

We never quite got there, of course. And Roosevelt failed to recognize that

handouts can have negative side effects, such as deterring some people from

trying to fend for themselves, or inducing some wealthy retirees to regard

Social Security as an absolute entitlement. Still, for most of the next half

century, most Americans agreed that people who worked hard or wanted to

work hard, and nonetheless fell on their faces, should be helped out.

The third provision of the social contract: Everyone should have an

opportunity fully to develop his or her talents and abilities through publicly

supported education. The national role in education began in the nineteenth

century with the Morrill Act, establishing land grant colleges. In the early

decades of the twentieth century a national movement swept across America

to create free education through the twelfth grade for every young person.

After the Second World War, the GI Bill made college a reality for millions of

returning veterans. Other young people gained access to advanced education

through a vast expansion of state-subsidized public universities and

community colleges. In the 1950s our collective conscience, embodied in the

Supreme Court, finally led us to resolve that all children, regardless of race,

must have the same—not separate—educational opportunities.

It is important to understand what this social contract was and what it was

not. It defined our sense of fair play, but it was not primarily about

redistributing wealth. There would still be the rich and the poor in America.

The contract merely proclaimed that at some fundamental level we were all in

it together, that as a society we depended on one another. The economy

could not prosper unless vast numbers of employees had more money in

their pockets. None of us could be economically secure unless we shared

the risks of economic life. A better-educated workforce was in all our

interests.

But the social contract is unraveling. Profitable companies no longer offer job

security. Now they routinely downsize their workforces, or resort to what

might be called "down-waging" and "down-benefiting." The term "layoff" no

longer means what it used to—most are now permanent, not temporary. We

need a new word to describe the new phenomenon. Perhaps we should call

them "castoffs." Companies are replacing full-time workers with independent

contractors, temporary workers, and part-timers. They"re bringing in younger

workers at lower wage scales to replace older workers with higher pay, or are

subcontracting the work to smaller firms offering lower wages and benefits.

Employer-provided health benefits are declining across the board, and health

costs are being shifted to employees in the form of higher copayments,

deductibles, and premiums. Defined-benefit pension plans are giving way to

401(k) plans with little or no employer contributions. About half of workers on

private payrolls have no employer-sponsored retirement plan at all.

Meanwhile, beginning in the early 1980s, American companies battled

against unionization with more ferocity than at any time in the previous half-

century. The incidence of companies illegally firing their employees for trying

to organize unions (adjusted for the number of certification elections and

union voters) increased from 14 percent in the late 1970s to 32 percent in the

early 1980s, where it more or less remained. This is one part of the reason

why the unionized portion of the private-sector workforce has plummeted.

The drive among American companies to reduce their labor costs is

understandable, given that payrolls constitute 70 percent of the cost of doing

business, and that pressures on companies to cut costs and show profits

have intensified. Competition is more treacherous in this new economy,

where large size and low unit costs no longer guarantee a competitive

advantage, and where institutional investors demand instant performance. Yet

it is also the case that the compensation of senior management,

professional, and highly skilled technical workers has escalated in recent

years. In large companies, top executive compensation increased throughout

the 1990s at the rate of over 10 percent per year, after inflation.

Top executives and their families receive ever more generous health benefits,

and their pension benefits are soaring in the form of compensation deferred

until retirement. Although they have no greater job security than others, when

they lose their jobs it is not uncommon for them to receive "golden

parachutes" studded with diamonds. The specter of Enron executives making

off with the company jewels while employees" savings disappear is only the

latest and most extreme example.

The second provision—a job paying enough to keep a family out of poverty,

and social insurance when no job is available—is also breaking down. The

real value of the minimum wage is now some 20 percent below its value in

the late 1970s. Unemployment insurance isn"t adequate for people

permanently laid off and in need of a new job. It was designed for temporary

layoffs during dips in the business cycle. And it doesn"t cover the ever-

growing number of workers who are employed part-time, or who move from

job to job. For those not covered by unemployment insurance and threatened

with destitution, welfare has traditionally offered an alternative. But even

before welfare "reform" eliminated that safety net in 1996, welfare payments

were shrinking in many states.

In fact the entire idea of social insurance is under attack. Proposals are being

floated for the wealthier and healthier to opt out. Whether in the form of

private "medical savings accounts" to replace Medicare, or "personal security

accounts" to replace Social Security, the effect would be much the same:

The wealthier and healthier would no longer share the risk with those who

have a higher probability of being sicker or poorer.

The third part of the social contract, access to a good education, is also

under severe strain. The federal government accounts for only eight cents of

every public dollar spent on primary- and secondary-school education in the

United States; states and localities divide the rest. As Americans

increasingly segregate by level of income into different townships, local tax

bases in poorer areas cannot support the quality of schooling available to the

wealthier. Public expenditures per pupil are significantly lower in school

districts in which the median household income is less than $20,000 than

they are in districts where the median household income is $50,000 or

more—even though the challenge of educating poorer children, many of

whom are immigrants with poor English language skills or who have social or

behavioral problems, is surely greater than the challenge of educating

children from relatively more affluent households. De facto racial segregation

has become the norm in schools in several large metropolitan areas.

Across the United States, public higher education is waning under severe

budget constraints. Tuitions are rising faster than median family income.

Meanwhile, elite colleges and universities are abandoning "need-blind"

admissions policies, by which they guaranteed that any qualified student

could afford to attend. Young people from families with incomes in the top 25

percent are three times more likely to go to college than are young people

from the bottom quarter, and the disparity is increasing.

Why is the social contract coming undone—especially at the time when it"s

most needed? Part of the reason has to do with the same basic forces that

have divided the workforce. Technological advances—primarily in information

and communication—and global trade and investment have made a big

portion of the tax base footloose. Capital can move at the speed of an

electronic impulse. Well-educated professionals are also relatively mobile.

They can move out of cities into remote suburbs where their property taxes

don"t have to pay for the costs of educating children poorer and needier than

their own. They can work from home offices or office complexes in the

country.

As a result of the mobility of capital and of the highly skilled, average and

poorer working people find themselves bearing an increasingly large

proportion of the cost of social programs—nationally, statewide, and in their

own towns. Yet, as noted, the incomes of most people in the bottom half of

the income ladder haven"t risen along with the growth of the economy. Most

are concerned with simply keeping their jobs.

Even this does not entirely explain the paradox. Today"s wealthier investors

and skilled professionals are not merely winners in a growing economy; they

are also citizens in a splitting society. Why would they now allow the social

contract to unravel? Are other forces weakening the bonds of affiliation and

empathy on which a social contract is premised?

I do not have a clear answer, but I do have two hypotheses.

First, in the new global economy, those who are more skilled, more talented,

or simply wealthier are not as economically dependent on the regional

economy surrounding them as they once were, and thus have less self-

interest in ensuring that their fellow inhabitants are as productive as possible.

Alexis de Tocqueville noted in his book Democracy in America that the better-

off Americans he met in his travels of the 1830s invested in their communities

not out of European notions of honor, duty, and noblesse oblige, but because

they knew they would reap some of the gains from the resulting economic

growth. "The Americans are fond of explaining almost all the actions of their

lives by the principle of self-interest rightly understood; they show with

complacency how an enlightened regard for themselves constantly prompts

them to assist one another and inclines them willingly to sacrifice a portion of

their time and property to the welfare of the state." Today, increasingly, the

geographic region within which a highly skilled individual lives is of less direct

consequence to his or her economic well-being. It"s now possible to be linked

directly by modem and fax to the great financial or commercial centers of the

world.

Second, any social contract is premised on "it could happen to me" thinking.

Social insurance assumes that certain risks are commonly shared. Today"s

wealthy and poor, however, are likely to have markedly different life

experiences. Disparities have grown so large that even though some of the

rich (or their children) may become poor and some of the poor (or their

children) will grow rich, the chances of either occurring are less than they

were several decades ago. The wealthy are no longer under a "veil of

ignorance" about their futures, to borrow philosopher John Rawls"s felicitous

phrase. They know that any social contract is likely to be one-sided; they

and their children will be required to subsidize the poor and theirs.

Should you care? Yes. Even if the poorer members of our society were

gaining a bit of ground while the richer were gaining far more, you might still

have cause for concern. After a point, as inequality widened, the bonds that

kept our society together would snap. Every decision we tried to arrive at

together—about trade, immigration, education, taxes, and social insurance

(health, welfare, retirement)—would be harder to make, because it would

have such different consequences for the relatively rich than for the relatively

poor. We could no longer draw upon a common reservoir of trust and agreed-

upon norms to deal with such differences. We would begin to lose our

capacity for democratic governance.

But even if you were willing to accept such dire consequences as the price

for improving everyone"s standard of living, you might not accept what"s

actually been happening. The economy has grown, inequality has widened,

and the rich have grown richer while the poorer members of our society have

been losing ground.

America as a whole is richer than it has been at any time in its history—

richer than any other nation in the world—richer, by far, than any nation in the

history of the world. And yet a significant portion of our population has

become poorer over the last two decades. We have a new class of full-time

worker. They"re called the "working poor." Although they work at least forty

hours a week, they don"t earn enough to lift themselves and their families out

of poverty. And behind the business cycle, the trend continues.

Global terrorism now poses the largest threat to our survival. But the widening

split between our have-mores and have-lesses poses the largest threat to our

strength as a society.

I don"t want to depress you; I want to alarm you. America is overwhelmingly

optimistic, practical, and innovative when it comes to solving big problems.

But that"s my point, really. Now"s the time to tackle this widening gap—to

reknit the social contract.

How? I offer a number of ideas in the pages to come.

Hey, Reich, you might say. You were in Washington. You were a cabinet

member in the Clinton administration. Why didn"t you and your friends fix this

problem? Well, we did raise the minimum wage, implement the Family and

Medical Leave Act, close sweatshops, get millions of Americans the skills

they need for better jobs, and get the economy back on track. But we didn"t

get everything done by a long shot.

The truth is, nothing happens in government unless citizens demand that it

happen. The real reknitting of the social fabric has to begin where the threads

are—where you and I both are. That requires, at bottom, that you, and I, and

millions like us get involved.

Many Americans have given up on politics. As their incomes have become

more precarious, they"ve lost confidence that the "system" will or can work in

their interest. That cynicism has generated a self-fulfilling prophecy.

Politicians stop paying much attention to people who are politically

apathetic—who aren"t involved. And the political inattention seems to justify

the cynicism. Meanwhile, big corporations and wealthy interests have

experienced the opposite—a virtuous cycle in which campaign contributions

have attracted the rapt attention of politicians, the attention has elicited even

more money, and that money has given the powerful even greater influence.

Don"t get me wrong. As individuals, many people on the winning side of the

divide are concerned about the new inequality. But as participants within

institutions committed either to preserving the status quo or gaining further

economic advantage for their constituents—large corporations, trade

associations, and assorted special-interest lobbies—their concern is often

laundered out of the politics they indirectly pursue. Reforming campaign-

finance laws will help. But such reforms alone won"t guarantee a vibrant

democracy.

Ultimately, there"s only one answer. You"ve got to get involved, personally.

Get on the phones. Get on E-mail. Get out the vote. Mobilize your friends.

Reach out. Build bridges across class and race. Persuade people to get

involved who haven"t been involved before. Convince good people to run for

office. Maybe run yourself. And then keep organizing and mobilizing.

The only way to reknit the social fabric is one thread at a time. The only way

to regrow democracy is from the grass roots.

"About this title" may belong to another edition of this title.

Other Popular Editions of the Same Title

Search results for I'll Be Short: Essentials for a Decent Working...

Ill Be Short Essentials for a

Seller: World of Books (was SecondSale), Montgomery, IL, U.S.A.

Condition: Good. Item in good condition. Textbooks may not include supplemental items i.e. CDs, access codes etc. Seller Inventory # 00042902751

I'll Be Short: Essentials for a Decent Working Society

Seller: Orion Tech, Kingwood, TX, U.S.A.

hardcover. Condition: Good. Seller Inventory # 0807043400-3-27673301

I'll Be Short : Essentials for a Decent Working Society

Seller: Better World Books, Mishawaka, IN, U.S.A.

Condition: Good. Former library book; may include library markings. Used book that is in clean, average condition without any missing pages. Seller Inventory # 11460374-75

I'll Be Short: Essentials for a Decent Working Society

Seller: ThriftBooks-Dallas, Dallas, TX, U.S.A.

Hardcover. Condition: Good. No Jacket. Pages can have notes/highlighting. Spine may show signs of wear. ~ ThriftBooks: Read More, Spend Less. Seller Inventory # G0807043400I3N00

I'll Be Short: Essentials for a Decent Working Society

Seller: ThriftBooks-Atlanta, AUSTELL, GA, U.S.A.

Hardcover. Condition: Good. No Jacket. Pages can have notes/highlighting. Spine may show signs of wear. ~ ThriftBooks: Read More, Spend Less. Seller Inventory # G0807043400I3N00

I'll Be Short: Essentials for a Decent Working Society

Seller: ThriftBooks-Atlanta, AUSTELL, GA, U.S.A.

Hardcover. Condition: Very Good. No Jacket. May have limited writing in cover pages. Pages are unmarked. ~ ThriftBooks: Read More, Spend Less. Seller Inventory # G0807043400I4N00

I'll Be Short: Essentials for a Decent Working Society

Seller: ThriftBooks-Dallas, Dallas, TX, U.S.A.

Hardcover. Condition: Very Good. No Jacket. May have limited writing in cover pages. Pages are unmarked. ~ ThriftBooks: Read More, Spend Less. Seller Inventory # G0807043400I4N00

I'll Be Short: Essentials for a Decent Working Society

Seller: ThriftBooks-Reno, Reno, NV, U.S.A.

Hardcover. Condition: Good. No Jacket. Pages can have notes/highlighting. Spine may show signs of wear. ~ ThriftBooks: Read More, Spend Less. Seller Inventory # G0807043400I3N00

I'll Be Short: Essentials for a Decent Working Society

Seller: Bay State Book Company, North Smithfield, RI, U.S.A.

Condition: good. The book is in good condition with all pages and cover intact, including the dust jacket if originally issued. The spine may show light wear. Pages may contain some notes or highlighting, and there might be a "From the library of" label. Boxed set packaging, shrink wrap, or included media like CDs may be missing. Seller Inventory # BSM.OBWJ

I'll Be Short-Essentials For A Decent Working Society

Seller: Foxtrot Books, Yankton, SD, U.S.A.

Hardcover. Condition: Good. Dust Jacket Condition: Good. Good Condition hard cover 121 pages. Seller Inventory # 030894